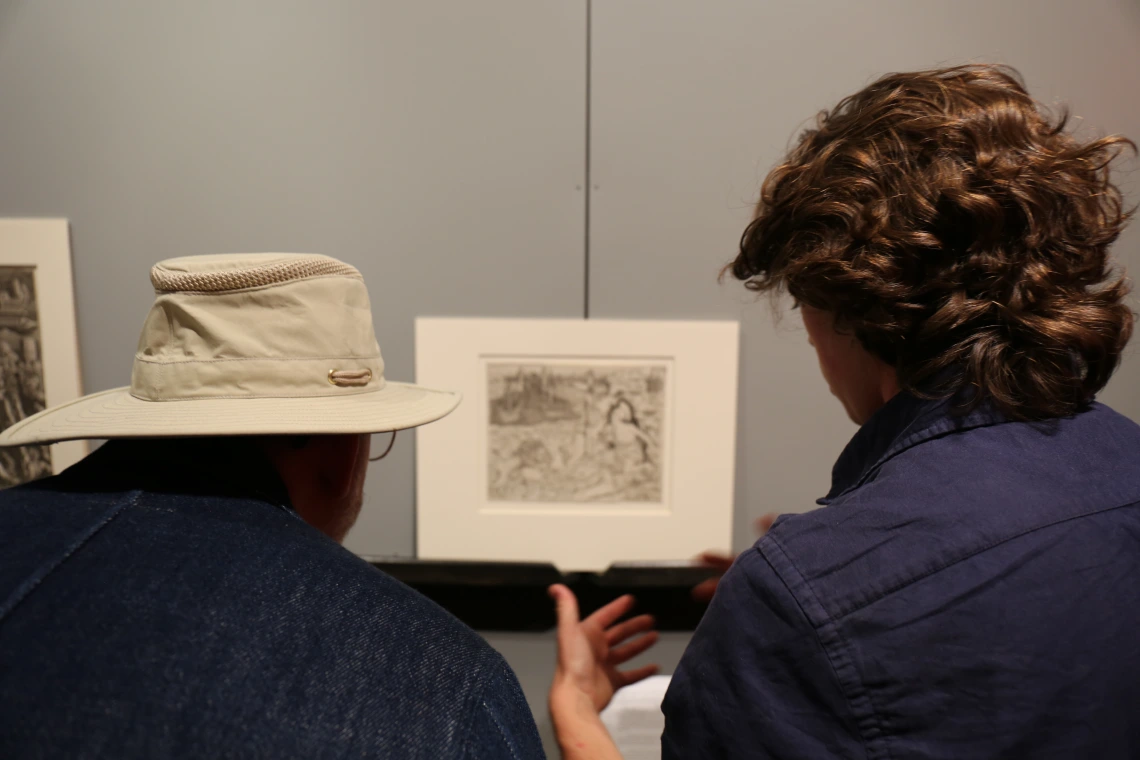

Manuela Maldonado Cadeñanes discusses her interpretation of the artwork with UA Museum of Art Director Olivia Miller.

In Aileen A. Feng’s seminar course ITAL 410 “Machiavelli and His Legacies,” students this semester went beyond their literary studies to research and interpret Renaissance prints from the University of Arizona Museum of Art collection.

As they worked through an in-depth study of Niccolò Machiavelli’s famous 1532 political treatise Il Principe in its original 16th-century language, the students also became guest curators, using the themes from their reading to analyze and interpret artworks made in Italy during the same time period.

The class then staged a pop-up exhibition, “L’occhio del Principe: Machiavellian Lessons Through Renaissance Prints,” on May 1 in the UAMA study classroom, featuring five prints from the museum’s collection, dating from roughly 1480-1650, alongside interpretive labels written by the students.

“Originally, I wanted to bring them to the museum so they could be immersed in visual art of the period we were studying, and to bring them to Special Collections so they could consult some of the earliest printed books out of Italy, including the first editions of Machiavelli’s works” Feng said. “But when I met with Willa (Ahlschwede) at the museum to talk about potential class visits and how to get my students really engaged with the collection, she said ‘Why don’t we do a pop-up exhibition?’”

Feng, Associate Professor and Director of Italian Studies, had already examined the museum’s catalog of more than 200 Italian Renaissance artworks and then for the pop-up she pre-selected 12 prints that presented themes the students would learn about as they studied Il Principe.

“This was a big ask because these are language and literature students, not art history students. They walked in thinking it was just an Italian literature class, and that their biggest challenge would be learning how to read Renaissance Italian, and now they had to learn about visual art and label writing for a museum,” Feng said. “They had to start thinking about Machiavellian themes very early in their reading and as we got later into the semester, they were really able to take ownership of their prints and bring something to their artworks that other curators wouldn’t necessarily think of.”

Ahlschwede, Assistant Curator of Education & Public Programs, said part of the museum’s mission is to create art experiences for all students.

“We work with a lot of students, frequently art and art history, but we strive to work with students beyond that, so we love these interdisciplinary connections. It’s an easy and natural fit with humanities students and how they’re learning to connect with all kinds of cultural artifacts,” Ahlschwede said. “It’s a special treat to pull prints out of our vault and work with students who can bring new insights.

The class took visits to the museum, looking at the permanent Kress Collection on display and receiving a primer on the art of the era and the transition from the Italian Middle Ages to Renaissance. They also learned how to write interpretive labels in a workshop with UAMA Curatorial Assistant Violet Arma.

The 11 student—Adrien Able, Sierra Beard, Nina Doering, Alex Gardner, Kate Jaramillo, Manuela Maldonado Cadeñanes, Stella Marcuzzo, Sadie Parent, Jairo Parra, Christian Schifano and Talia Tardogno—then worked in teams, selecting five of the prints Feng presented to them, writing interpretive labels for the pop-up exhibition.

“They each brought something from their own academic backgrounds and perspectives, so they had different engagements with the prints and were able to learn things from one another too,” she said.

Tardogno and Beard chose Ugo da Carpi’s David Slaying Goliath, a chiaroscuro woodcut from 1518. In Il Principe, Machiavelli praises David for only relying on his slingshot to defeat his opponent rather than borrowing the weapons of others. In the woodcut print, David appears holding a sword over Goliath, rather than with his slingshot, already having downed the giant.

“This represents a part of the battle that’s not usually shown and it signifies triumph and victory,” Tardogno said. “We related it to Machiavelli because in Machiavelli’s ideals, to be a good prince or leader, you have to rely on your own weapons. David [with his slingshot] embodies this ideal that to overcome challenges, you have to do it yourself.”

Beard said the project was daunting at first, but as they developed a deeper understanding of Machiavelli’s text, they realized the artwork became a helpful way to analyze themes like virtù and fortuna, which don’t have single-word meanings.

“With Italian, there are concepts that can’t be translated as easily into English,” she said. “And this print represents some of those.”

Jairo Parra and Christian Schifano present their analysis of 'Naval Battle Between the Greeks and Trojans.'

Schifano and Parra chose Naval Battle Between the Greeks and Trojans, an engraving from 1538 by Giovanni Battista Scultori.

“What attracted us was the pure detail of the engraving,” Schifano said. “There are so many intricate things that you could stare at for hours. It really tells a complete story.”

Though it depicts a chapter of Homer’s Iliad, their analysis centered on Machiavelli’s analogy of a fox and a lion as two personas a prince must have, with the fox representing cunning and cleverness, and the lion representing strength and power.

“When we saw this engraving, we thought about how it connects to Machiavelli talking about a battlefield and war,” Parra said.

The pop-up exhibition drew 64 visitors, including Ken McAllister, College of Humanities Associate Dean of Research and Program Innovation, who said it was impressive to see the students so engaged with their work, and so supportive of each other.

“As an archivist, I was delighted to see students beginning to understand the often tricky art of producing interpretive materials for an exhibition. Though brief, this practice will stay with these students for a lifetime I suspect. They'll never visit a museum or gallery again without thinking, if just for a second: "Someone made these signs and labels, and to do that, they had to think through a bunch of issues and make decisions about how best to invite viewers into the experience of a piece,’” he said. “It was a brilliant event that reminded me yet again that COH faculty are life changers and world makers.”

Adrien Abel (right) discusses his print with COH Associate Dean Ken McAllister.

Feng said that when she teaches the course again, the UAMA collaboration and pop-up exhibit will become a permanent part of the class.

“It gave students an opportunity to critically engage with cultural objects they don’t normally study in an Italian literature class and to apply their specialized knowledge about a political treatise to artworks of the same period,” Feng said. “They have developed an expertise and a skill set that can be applied to many different media.”